Submissions close today on proposed reforms that would mark the most significant shakeup of fisheries in decades. Here’s what you need to know.

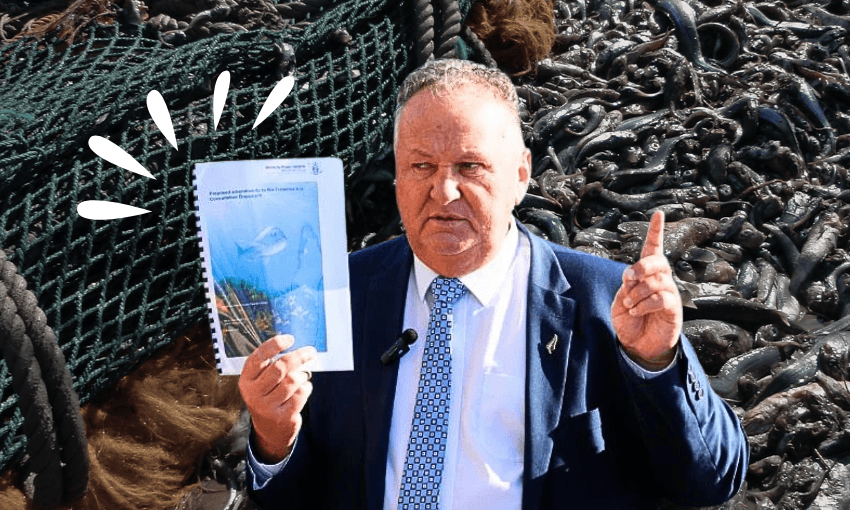

On February 12, oceans and fisheries minister Shane Jones held up a wagging finger and a shiny, plastic-comb-bound document as Wellington’s downtown seagulls squawked overhead. Among a throng of media and fishery sector executives, he announced a proposal to make changes to the Fisheries Act – changes that he said would be the most significant reforms in decades. This act is the primary way that our wild-caught fisheries, which generated more than $1.6 billion in export revenue in 2024 and employ about 9,000 people, are regulated. Its main purpose is to manage commercial fisheries while ensuring sustainability.

Jones touted the changes as an acknowledgement that “red tape” needed to be cut to “improve responsiveness, efficiency and certainty” and that the industry needed protection from being “charged on TikTok”. While the proposed changes were welcomed by industry, responses from opposition parties, scientists and advocacy groups have been mixed. While the most significant changes proposed pertain to the Quota Management System, which controls how much of each fish species can be caught each year, media attention has largely focused on privacy measures relating to the footage captured by cameras on fishing vessels. The strongest public reaction has been from LegaSea, a recreational fishers’ advocacy group, which has called the proposed changes a “scam”. Meanwhile, groups like the Environmental Defence Society are sharing their formal legalese submissions. A phrase that repeatedly comes up is “no supporting evidence”.

The government is currently seeking feedback on the proposed changes, with submissions closing at 5pm this Friday. If you can’t be arsed reading that document that Jones was waving around underneath the seagulls, here are its main points.

Changes in how catch limits are decided

Under the Quota Management System, the government sets total allowable catch limits for 642 fish species. This limit is split into customary Māori fishing, recreational fishing and commercial fishing. The proposal document says there is now better-quality and more frequent data through reporting by fishers, onboard cameras and fisheries observers, which means decisions on catch limits can be more responsive, efficient and certain. It proposes the minister be allowed to approve up to five years’ worth of catch limits through one decision, with year-on-year increases. Currently, the minister decides on one annual catch limit at a time.

In a webinar on Monday, Environmental Defence Society (EDS) solicitor Tracey Turner said the society supported the intent of these proposed amendments because the current process for adjusting catch limits is lengthy and resource intensive. However, she said the proposed process had “inadequate safeguards” and there wasn’t enough information to support adjustments. She suggested more investment in fisheries science and stock assessments was needed.

Another proposal is to streamline management procedures for certain fish stocks, with pre-agreed procedures for how and when catch limits could be adjusted that would bypass the current high-level review each year. When monitoring showed a certain level of biomass (fish in the sea), catch limits could be adjusted accordingly.

The Environmental Defence Society is not supporting this proposal. On Monday, Turner said that when a similar approach was used to manage rock lobster, the fisheries data used turned out not to be a reliable indicator of abundance. Even as their numbers were declining, the fisheries data did not show a reduction, and so rock lobster were over-fished.

Greater recognition of socio-economic factors when setting or altering catch limits

The proposal says that social, cultural and economic factors have been considered alongside biological matters since the introduction of the Fisheries Act in 1996. For example, biologically speaking it may be better to set a limit of zero for a year to allow a fish population to recover, but because people’s livelihoods and diets depend on this fish, fishing has been allowed to continue at lower levels for a few years. The proposed amendment is to change the wording to reflect the inherent trade-off when deciding the level of fishing and time to rebuild population.

The Environmental Defence Society did not support this proposed change either, with Turner saying the change would “create risk that monetary impacts, that are always more easily quantified, would be given more weight in decision making”.

More recognition of non-regulatory sustainability measures

The proposal document puts forward two options to clarify the minister’s ability to consider non-regulatory (voluntary) sustainability measures when deciding on changes to regulations like setting catch limits. Option one is to provide the minister with discretion to recognise any non-regulatory measure, meaning they could choose to take them into account or not. Option two is that the minister must consider ACE (annual catch entitlement) shelving (when quota owners reduce their catch of a stock) and catch spreading (when fishers agree to gather fish from a specific area).

The document says that while non-regulatory measures can be helpful and lower administrative burden on the government, they are risky as they can’t be actively enforced. It says the effectiveness of some measures is uncertain. For the EDS, this was also a no.

Increasing how much of a quota can be carried forward

At the moment, if a fisher does not catch their full entitlement in a year, they can carry forward up to 10% (for most fish species) of their allocation into the next year. Option one is a proposal to increase this to 15%. Option two is to grant the same increase but only in exceptional

circumstances (for example storm events). The EDS submission said there was no supporting evidence for these changes, and they did not adequately consider the impacts on species and ecosystems.

Greater protection for on-board camera footage

At the moment, footage from fishing vessel on-board cameras is subject to release under the Official Information Act, meaning members of the public can request it. The document says there are fisher concerns about the potential for commercially sensitive information to be released and legal fishing activity used to negatively impact industry reputation. There are two options presented here. The first is to check processes with the ombudsman to make sure obligations are being met. The second is to exempt the footage from the OIA, meaning that footage would not be able to be requested.

This second option, which fisheries minister Shane Jones has said he favours, has generated opposition. WWF-New Zealand’s Kayla Kingdon-Bebb told The Post, “Greater transparency and accuracy in the reporting of protected species bycatch and non-target discards is incredibly important to ensure the sustainability of our marine resources now and into the future.” LegaSea’s Sam Woolford added, “How can we take this proposal to limit transparency seriously?”

Amendments to the scope of on-board cameras

At the moment two types of fishing vessels are excluded from monitoring cameras: deepwater trawl vessels over 32 metres long or that exclusively target scampi, because observers are considered a more efficient way of monitoring; and small set net vessels (less than 8 metres in length) because they have very limited on-board electronics and dry space. The proposed changes would also exclude bottom longline vessels over 31 metres long, because they have fisheries observers; set net vessels using the mothership and tender models and all vessels less than 8 metres as it is not currently possible to install cameras on these. Not developing bespoke solutions would save costs.

Clarifying camera use requirements

At the moment, cameras must be active for fishing activities including the taking, return, abandonment, processing, sorting and transportation connected with monitored fishing, as well as while measures to avoid, remedy or mitigate fishing-related mortality were being carried out. The proposed changes seek to clarify that. Option one proposes that cameras operate port-to-port. – meaning cameras would operate continuously from when a vessel left port or entered a fishing area, to when they returned to port or left the area. Option two proposes that cameras be active when conducting a fishing event using an in-scope method, sorting, processing or returning to the sea any fish taken during a fishing event using in-scope methods and transiting to, from and between fishing locations when using in-scope methods.

In a written submission provided to The Spinoff, the Environmental Law Initiative (ELI) opposed option two, on the grounds that there are strong public interest considerations that apply to the footage, including promoting transparency and accountability. The group is particularly concerned that option two would prevent researchers from accessing footage for research purposes. ELI does not believe that exempting the footage from the OIA is necessary to address privacy concerns.

Landing and returning fish

This part of the proposed changes is about fish that fishers catch unintentionally (bycatch). In 2022 the act was amended to tighten when fish can be returned (thrown back into the sea) to encourage commercial fishers to minimise bycatch. At the moment, the minister can permit that fish be thrown back only if there’s an acceptable likelihood of survival, if keeping it will damage the rest of the catch, if it is damaged or if the return is for biological, ecosystem or management purposes (eg. if a lobster is carrying eggs).

The proposal suggests that new, more effective monitoring, particularly with cameras, gives an opportunity to consider more flexible rules, so suggests amending the act to allow returns, dead or alive, as long as they are monitored by on-board cameras or observers. Because the returns would be observed, they could be considered and counted for the fishers’ annual catch entitlement.

EDS’s main concern with these amendments is a lack of incentive to minimise or avoid bycatch. They believe that reforms should incentivise improved selectivity – ie encourage fishers to use methods that target only certain fish. They also question whether on-board camera footage is good enough to verify fisher reporting.

What’s next?

After the consultation closes on Friday, submissions will be reviewed by the Ministry of Primary Industries. Then the policy will be refined, key stakeholders will be consulted, a Regulatory Impact Analysis will be conducted and the updated policy proposal will be presented to the minister. If the minister is happy, he will then take it to cabinet and then the legislation will be drafted and introduced to parliament. In the announcement in February, Shane Jones said he expected the legislation to be passed before the 2026 election.